In the pre-dawn chill of November 18, 1977, Laura Monroe, a 28-year-old patrol sergeant in Pacifica, California, kissed her husband Jack goodbye and headed out for her night shift along the foggy cliffs of Highway 1. Her crisp blue uniform and gleaming badge marked her as a rising star in a small-town police department, one of the few women to earn sergeant stripes in a male-dominated force. She promised to be careful, flashing a smile that lingered in Jack’s memory. That was the last time he saw her. For 13 years, Laura’s disappearance haunted Jack, the Pacifica PD, and their coastal community. In 1990, a fisherman’s shocking discovery of her rusted patrol car at the base of Devil’s Slide—a treacherous stretch of coastline—unearthed blood, a bullet casing, and a web of corruption that reached the heart of the department. A heart-shaped pendant, engraved with their love, would lead Jack to a truth more devastating than he could have imagined.

Laura Monroe was no ordinary cop. At 28, she’d already shattered glass ceilings, earning her promotion through relentless dedication. Her personnel file painted a picture of a woman who lived for the badge: meticulous logbooks, glowing reviews, and a reputation for fairness. She and Jack, a fellow officer, had built a quiet life in Pacifica’s modest neighborhoods, their home filled with dreams of a future family. That November night, Laura’s logbook recorded a routine traffic stop at 8:15 p.m. near mile marker 42 on Highway 1—a desolate spot by Moss Landing’s industrial docks. No distress call followed. No backup request. Just silence. By morning, her 1975 Plymouth Fury patrol car was gone, and so was she.

For years, rumors swirled. Some whispered Laura had fled the pressures of the job or her marriage, a theory Jack rejected but couldn’t disprove. The department searched tirelessly at first, combing cliffs and docks, but 1970s technology offered no leads. Her radio and dash cam were missing, her bank accounts untouched. Jack, a sergeant himself, clung to her personnel photo—blonde hair feathered, blue eyes bright—and scoured case files annually, finding nothing but dead ends. The Pacifica PD scaled back, leaving Jack and the community to mourn a mystery that refused to yield.

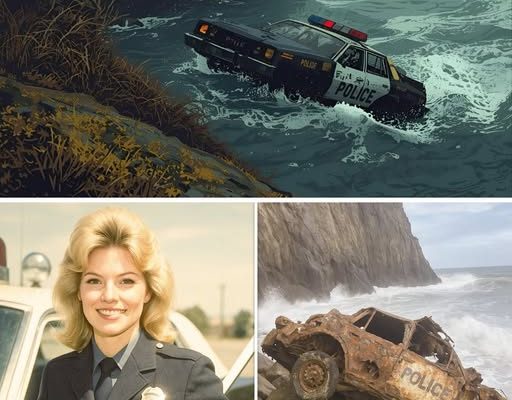

On a foggy March morning in 1990, everything changed. Sergeant Jack Monroe was sipping coffee when his radio crackled: a fisherman had spotted a rusted police vehicle at Devil’s Slide’s base, where cliffs plunged into the Pacific. Jack’s heart sank. He knew before dispatch confirmed it—only one patrol car had vanished in Pacifica’s history: Laura’s. Racing to the scene, he joined Detective Marie Estrada, a sharp, empathetic investigator with a knack for cutting through chaos. From the cliff’s edge, they saw it: a mangled 1975 Plymouth Fury, its chrome bumper glinting through the haze, barnacles crusting its frame like scars.

The Coast Guard helicopter lifted the wreck with agonizing care, water streaming from its shattered windows. On solid ground, the car was a relic of decay—rust-eaten, seats rotted to springs, dashboard corroded. Forensics moved in, cataloging a corroded flashlight, a fused citation book, and then, chillingly, a .40-caliber brass shell casing—department issue. Blood traces, degraded but undeniable, coated the back seat and trunk. Jack’s knees weakened, but he stood firm, watching as the vehicle’s VIN confirmed it: this was Laura’s car. The scene was no accident—it was a crime.

Richard Hensley, the department supervisor and Laura’s boss in 1977, arrived with a practiced air of concern. Now in his late 50s, his authority still commanded the scene, but his quick dismissal of the evidence—suggesting Laura might have shot someone and fled—grated on Jack. “That’s not Laura,” Jack snapped. Marie, sensing his pain, promised to lead the investigation with rigor, urging Jack to step back. Reluctantly, he agreed, retreating home to pore over Laura’s 1977 case files, a box of memories marked “L. Monroe, 1977.”

At home, Jack spread the files across his office floor, Laura’s photo staring up at him—her proud smile a reminder of her ambition. Her logbook showed her last entry: a traffic stop at 8:15 p.m. Her partner, Officer Patricia Hris, had seen her at 8:00 p.m., cheerful and planning to catch a late movie. Two civilian witnesses reported a patrol car on Highway 1, but details were vague. The duty roster caught Jack’s eye: Deputy Carl Bowen, night supervisor, had signed off on Laura’s log. A name from the past, now with San Mateo County. Jack called Marie, who promised to track Bowen’s contact.

Driven by instinct, Jack retraced Laura’s patrol route, stopping at mile marker 42. The desolate spot—scrub brush, wind, and distant docks—felt unchanged. A patrol car approached, and to Jack’s surprise, Carl Bowen leaned out, gray-haired but alert in his San Mateo uniform. “Heard they found Laura’s car,” Bowen said, his sympathy guarded. When Jack mentioned the logbook, Bowen’s eyes flickered, his excuse—routine sign-off—too smooth. He suggested coffee later, claiming a shift in San Pedro Valley Park, and drove off. Jack’s unease grew.

At the station, Jack spotted Hensley pacing outside, his phone call heated: “The car came up. Your job, move now.” Hensley’s forced explanation—EPA regulations for the car’s transport—felt hollow. Inside, forensics reported the blood samples were too degraded for quick DNA results, but the bullet casing matched Laura’s service weapon. Jack’s suspicion deepened. Why was Laura alone that night, against protocol? Who had assigned her that isolated route?

Marie uncovered a misfiled witness statement from Belinda Carlson, a park ranger in 1977, describing a female officer stopping a white van at Devil’s Slide. A second, official statement from Carlson claimed she saw nothing. The contradiction screamed cover-up. At Carlson’s Fairmont home, they caught Hensley handing her an envelope, his demeanor aggressive. Carlson, shaken, admitted Hensley paid her $3,000 to lie in 1977, claiming her original statement about the van was “confusing.” She’d seen Laura stop a white van at 8:30 p.m., then spotted it again near San Pedro Valley Park at 12:30 a.m., its crescent-moon dent unmistakable. Hensley’s bribes and threats—costing her ranger job—kept her silent for 13 years.

Following a lead, Jack and Marie tracked Bowen to San Pedro Valley Park, spotting his and Hensley’s vehicles. Hiding, they watched the men carry a shovel, gear bag, and a black plastic bag to a crate. Hensley’s panic was clear: “They found the car, Carl. Blood, bullet casings, DNA testing.” Bowen dismissed the risk, revealing Laura’s body was buried at Middle Peak. They planned to move it to frame “business partners.” Following Bowen to Sharp Park Water Treatment Facility, they saw him bury human remains—bones, fabric, hair—and pocket a finger bone as a trophy.

The scene escalated when Bowen entered an abandoned shed, emerging with a drug package and two terrified teenage girls. Jack and Marie called for backup, uncovering a meth lab and human trafficking operation protected by corrupt cops. A white van, matching Carlson’s description, confirmed the link to 1977. SWAT arrested Bowen and his associates, rescuing the victims. Back at the station, Hensley confessed: Laura had stopped a meth-running van. Wounded by the driver, she was killed by Hensley to silence her, her body buried, her car dumped. The operation grew, with cops like Bowen profiting from drugs and trafficking.

In the evidence room, Jack held Laura’s heart-shaped pendant, engraved “Jack and Laura forever.” Tears fell as he confirmed her remains. Carlson’s testimony, the pendant, and the arrests dismantled the department’s corruption. Laura’s death exposed a betrayal that shook Pacifica, but her legacy—through the rescued victims and Jack’s resolve—restored the badge’s honor. After 13 years, justice surfaced, like her car, from the depths.